| |

| Cutting Panels to Size |

|

Outdoors, I rough-cut a sheet of 3/4"

thick MDF into smaller pieces

using a circular saw and straightedge. The pieces were cut a little

larger than needed.

After this rough cutting, I took the

pieces to my table saw to cut down to final size. I built a crosscut sled for

my table saw that helps keep cuts square, as well as

providing a handy stop so that sequential cuts are almost identical in

width. Click the picture on the left to enlarge the crosscut sled photo. |

| |

| Joining with Biscuits for

Good Alignment |

|

While there are many ways to assemble

cabinets accurately, I prefer using biscuits. A slot is cut on the

mating surfaces of two or more pieces, and a flat, pressed-wood biscuit

is inserted into the slot to key the pieces together. Accurate layout is

needed, and when cutting slots, I always register on the outside surface

of each piece. |

|

I've constructed a jig for my

Porter-Cable biscuit cutter that speeds this work. The pieces being cut

rest on a large flat surface instead of the small fence of the biscuit

cutter. Here, I'm holding a piece about to be cut with another piece for

safety. I don't like to have my hands close to the cutter in case

something slips. |

|

The faces of some panels are cut with

slots, while the edges of other panels have them. This photo shows slots

being cut into the face of panel. I

deviated a bit from John Krutke's plans for the cabinet - I wanted to

have the sides of the sub continuous (no joints), and to have all the

joints come together on the top and bottom panels. I can then

double-veneer the top to keep the joints from telegraphing. Since the

bottom doesn't really count, having only one surface with all the joints

on it means less work when finishing. |

|

To allow for a compressed gasket, I

placed a piece of stout cardboard on a piece of MDF to space the slots

for the baffle mounting frame accurately. I couldn't use my biscuit

cutting jig here, but it's still a big surface on which to rest the

biscuit cutter. |

| |

| Assembling the Amp Box |

|

To ensure that the amp box parts are all

exactly the same width (desired for good air sealing), I used a

smoothing plane on them. Clamped together on a flat surface, the plane

shaved them to the same dimension. |

|

The sealed space for the amplifier was

created by the poplar boards glued and

screwed into an H frame. |

|

When the H-frame was dry, it was glued

to the back panel. I used no biscuits here because I couldn't easily

figure out how to register them. Besides, the long ends of the H frames

would also be glued to the top and bottom anyway, and that's

sufficiently strong. In this

picture, I had already used a Bosch jigsaw to cut out the opening for

the amplifier on the back panel. |

|

Once the H-frame was attached, I cut a

piece of 1/2" baltic birch plywood to cover over the space. |

| |

| Marking Amp Box Mounting Holes |

|

With the plate amplifier centered and

taped temporarily in position, I used transfer punches to mark the

locations of the mounting screws. Once marked, the amp was removed. |

| |

|

Assembling the Baffle Mounting Frame |

|

A rectangular frame of poplar wood

recessed into the box provides a mount for the baffle. Small "face frame"

(FF)

biscuits were used to join the frame. Larger #10 biscuits hold the frame to

the inside of the cabinet. That puts them in shear for the baffle

mounting load, which is ideal. |

|

The baffle mounting frame was glued

together as a sub-assembly. Five-pound lead weights helped maintain a

level face for the glue-up. I was very careful to maintain squareness

during glue-up. I checked it with a 12" Starrett combination square just

after clamping, and made small adjustments until perfect. |

| |

| Brace Fabrication |

|

John's design uses a unique set of

internal braces made from 2x2 lumber. His design information gives an

explanation, and he claims that it is ideally suited for a symmetrical box like

this one. It IS easy to fabricate these braces! |

|

After cutting the 45* miters on each end of

the braces, I used a drill press to cut counterbores

for the screw heads and then drill the through-hole. I used a Forstner bit for the

counterbores, and then

used the "dimple" left in the center as a guide for the

through-hole. I used a drill press fence and fence stop to aid this

work. If limited to a simple hand drill, I'd just drill the

through-holes and forget the counterbore. |

| |

| Inserting Baffle Mount T-Nuts |

|

I purchased 1/4-20 T-Nuts from a local

hardware store for the baffle mount. The T-nuts have prongs that

penetrate into the wood to keep them from spinning when bolts are

tightened. I press them in using a c-clamp, and use a little Gorilla

glue to ensure that they don't pop out. |

| |

| Baffle Fabrication |

|

Every cut is drawn onto the surface

before routing. It reduces the chance for mistakes. I use my old

drafting compass with an extension beam for this work.

After layout, I drill a 1/8" hole at the

center of each circle for the circle jig pin. Usually I do this on the

drill press to ensure a hole square to the surface, but this

baffle was too big for my drill press to "reach" into the center. I use

a hand drill instead with a simple block of wood to aid drilling the

hole straight. See a photo of the wood block on a drill further down the

page. The block of wood has been drilled square on the drill press, and

it works fairly well as a guide. |

|

Routing MDF is messy. I try

to do as much routing outdoors as possible. I can use a leaf blower to

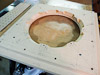

clean up afterwards. Shown is the

large Jasper Circle Jig on a Bosch plunge router. A 1/8" pin serves as

the center of rotation for the router with jig attached. One baffle

front is shown in the background of this picture with the driver recess

and through-hole already cut. The inner baffle is shown about to be routed.

I use a 1/4" spiral upcut bit to cut the

through holes. The bits are Bosch brand, purchased from Lowe's. I had

trouble with Freud bits in the past. Each cut is about 1/8" deep, and

they progress until the hole is through. The turret-style depth stop on

the Bosch router is ideal for incrementing these cuts ever deeper. |

|

For this job, I used double-stick tape

to hold the pieces to a backing board for cutting. The tape's purpose is

to prevent the center piece from coming adrift when I cut through the

MDF, which may cause an unplanned divot cut into the part. The backing board, of course, prevents the router from cutting into

the work table. |

|

To mount the driver, I'll use hurricane

nuts on the back side of the baffle. To mark the holes for their

location, I shimmed the driver to the center of the recess using pieces

of cardboard, then lightly punched dimples into the MDF using a transfer

punch. The punch centers on the driver's screw hole for an accurate

layout. The driver must not move between punches in different holes, and

the shims combined with a 25lb driver were sufficient. |

|

To provide sufficient airflow around the

back of the driver, it's customary to cut relief chamfers into the back

of the baffle. Full thickness is needed in the lands where the hurricane

nuts will be pressed in, but the in-between areas need to be chamfered

away. In pencil, I marked the future location of the hurricane nuts so that I

knew where to stop cutting. |

|

A router table with a 45 degree chamfer

bit cut the chamfers. A handheld router could be used, but a router

table allows a little more control. I had built this router table last

summer, and I was determined to put it to use. |

|

A picture showing the chamfered areas

between the hurricane nut "lands" during cutting. Note the ultra-fine

sawdust from the MDF. I had a shop-vac attached to the router table, but

it's not 100% effective. It helps, though. |

|

The chamfers are complete. Especially

needed in thick baffles, chamfering aids the airflow behind the driver. |

|

This detail shows how I had

pin-registered the inner baffle to the outer baffle. This was done prior

to routing the holes so that I could work with the pieces separately.

Then, when routing was done, the two baffles lined up perfectly again

when assembled together.

I put two pins in the baffle on opposite

ends of one of the diagonals. Pins locate better than screws, which

serve merely to clamp the two pieces together. Note that the pins were

already in place when I routed the chamfers in the driver cutout, but I

didn't show this detail in an earlier step.

I purchased the 1/8" steel pins in a box

of 100 from

McMaster-Carr online. They also serve double-duty as spare pins for my

Jasper circle guide. |

|

I checked the alignment of mounting

holes for three mating items - the baffle mounting frame (shown on top here),

the inner baffle which nestles inside the cabinet, and the outer baffle.

All screws went in fine without serious binding that might be caused by hole location

mismatch. I was a little concerned about matching up three pieces well

enough, but

it turned out OK. |

|

Time to press in the hurricane nuts that

hold the driver to the baffle. Again, I used a c-clamp to squeeze them

into their appropriate holes, and I added a couple drops of Gorilla glue

to make sure they don't spin in place when screws are inserted.

Note the use of an old plywood 90 degree jig to hold

the baffle upright for this operation. It seems that I never throw anything away, and

some unused things come in handy even after years of gathering dust. |

| |

| Gluing the Cabinet Together |

|

Dry Fit: The first task before gluing

everything together is to do a test fit without glue - a "dry fit". The

biscuits make this a "snap-together" test. They hold things in position

well enough so that I don't have to juggle a pile of loose parts. |

|

Here's a chance to assess the fit of

mating parts before gluing. A tight-fitting joint is desired, and all

joints in this project looked fine like the picture shows. After the

check, everything is taken apart again for gluing in steps. I usually

glue up subassemblies in larger projects like this one. |

|

In this photo, the rear panel and the

bottom panel are being glued together. I used the right side panel, with

biscuits in it, to align the bottom and rear panels correctly. A piece

of waxed paper placed at the joint prevented the bottom/rear subassembly

from gluing itself to the right side at this time. Not shown in the

photo is that I also snapped on the other side panel (would be located

on the top at this orientation) to also locate the glued panels for

assembly. |

|

After the two panels shown above had

dried, I then glued and clamped the baffle mount frame to the bottom

panel. The other panels pictured are there merely to have their biscuits

align the assembly in the proper location for drying. Slips of wax paper

keep squeezed-out glue from sticking to the panels used to register the

assembly. After the glue dries on the other panels, they were

removed, and glued together later in separate steps. |

|

When the baffle mount frame glue had

dried from the previous step, the top panel was then glued to the

subassembly. I am getting ready to glue in this step, and the panel

partially shown on the left of the photo would be used to register the glued

pieces to keep things square. The panels themselves become part of an

assembly jig. |

|

Because one side was still detached, I

had ample room to start adding some of the internal 2x2 bracing with screws and glue. It was

easier at this point because there was room to work, but I could

have waited until the end. There are

still more braces to attach, but that can't be done until after final

panel is glued on. |

|

Regardless of the care taken beforehand,

there are always slight mismatches between adjacent surfaces after

gluing. I used a small block plane here to quickly level a small

mismatch between two adjoining panels. It's faster than sandpaper, and

likely more accurate because of the dead-flat bottom on the plane. |

|

The final panel is glued on. Not all clamps are shown

in position yet. I still had to attach several small 6" clamps to the

interior baffle mounting frame to secure it against the inside of the panel

shown at the picture's left. |

| |

| Final Assembly Details |

|

Attaching the plate amplifier to the

back: drilling pilot holes square into stock without a drill

press is challenging. To provide a "portable guide", I pre-drill a clearance

hole in a small block of wood with my drill press. To use it, I put it

on the hand drill with bit, position the point of the drill in a

punched "dimple", slide down the wood block until it's flat against the

surface to be drilled, and that guides the drill in straight.

I prefer to use German-made Colt drills (when

possible) with wood or MDF. The brad point of the drill reduces bit wander when

drilling deep holes, and they are very well made. Unfortunately, they have

only 1/32" increments between sizes. I'd prefer to have 1/64"

increments. They still got the job done nicely for these pilot holes though. |

|

Installing gasket material onto the

driver. I used Parts Express #260-542 speaker gasket tape. It comes

in a 1/8" thick x 1/2" x 50 ft. roll. Tip for first-time

users: it won't bend around curves until you remove the paper backing. |

|

I used #10-32 flat head socket screws

(1-1/2" long) to mount the driver to the baffle. The driver mounting

ring counterbore for the screw head measured 0.390", and the #10 FH

screws have a 0.385 diameter head. That provided a nice, tight fit. [I

don't remember if I had to enlarge the hole in the driver rim to clear

the #10-32 threads.] |

| |

| First Sound |

|

First impressions: It is a BIG box. It

weighs about 70 lbs, and I

wrenched my back moving it into position. The sound is impressive though. It digs deep enough to make my pant

legs flap in the breeze when playing bass-heavy material like

Herby Hancock's Dis is Da Drum or Virgil Fox's The Bach Gamut

organ music. There's some rolling, deep bass in Beats Antique's

Tribal Derivations (track #6 - Derivation) that becomes very

audible with this employed. It's not just audible, it's tactile enough

to feel. In some cases, it makes your head feel funny.

I haven't trimmed the baffle edge flush with the

sides of the cabinet yet, so it's very ugly right now. I won't trim it

until I know whether I will paint or veneer the cabinet. Veneering adds

thickness to the box, so a flush trim of the baffle at this point would not be flush after veneering. Paint

is cheaper, but requires a lot of prep time. Decisions... |

|

My big problem now is where to put it in

my room. It commands attention out in the open. One option I'm

considering is to make it into an end table, with the driver firing

downward. I'd likely have to move the amp to an external location on the

equipment rack and probably build separate box for it. If I chose this

route, I'd fabricate a table top from solid wood

and attach it to the subs' current back side. The back would then become the top. I've seen very nice, furniture-quality examples of

this approach on the internet, but it would be a lot of work to do.

Finishing always takes longer than building! |

| |

|

| |

|